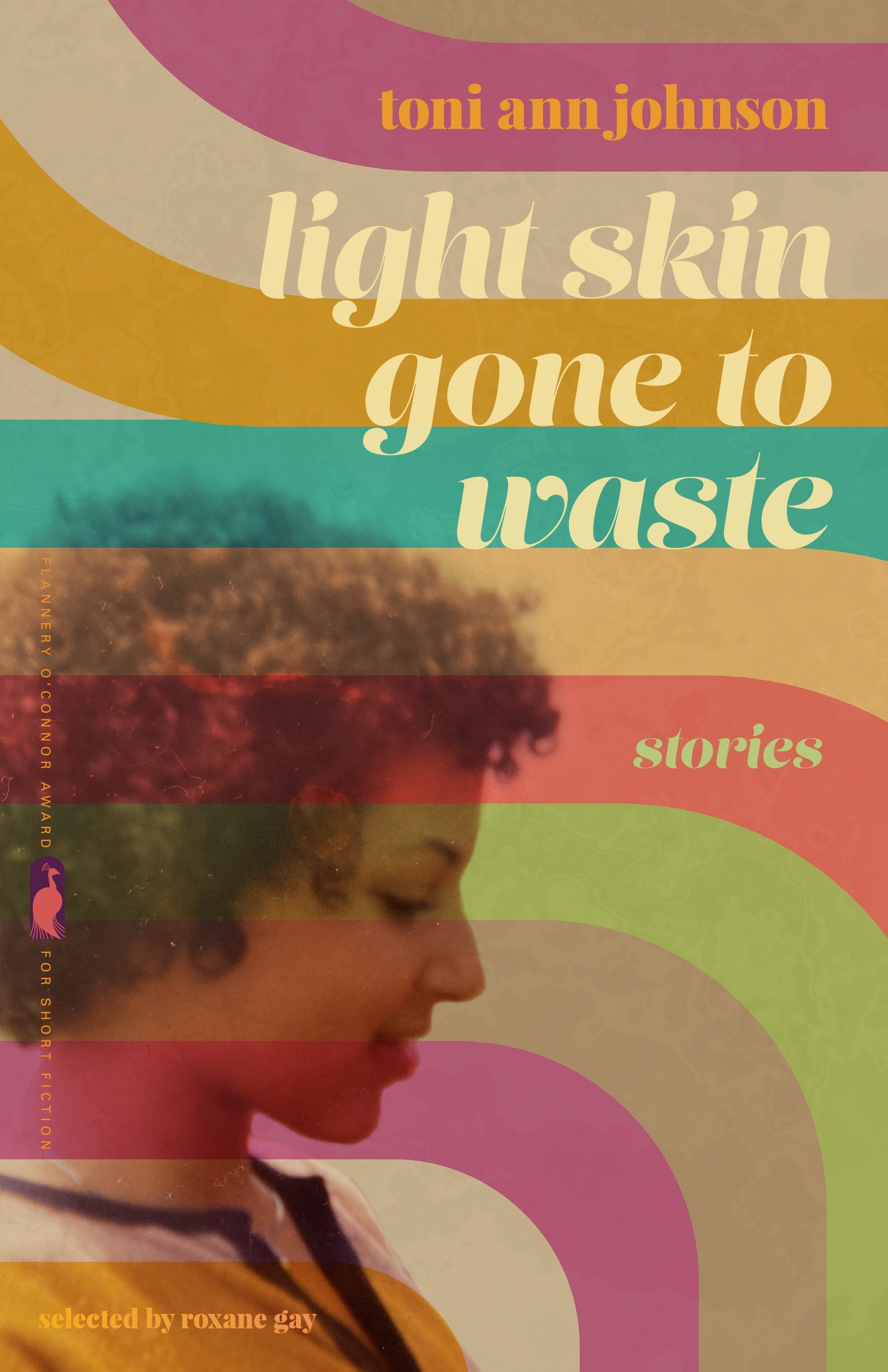

LIGHT SKIN GONE TO WASTE

A Collection from Kimbilio Fellow Toni Ann Johnson

In 1962 Philip Arrington, a psychologist with a PhD from Yeshiva, arrives in the small, mostly blue-collar town of Monroe, New York, to rent a house for himself and his new wife. They’re Black, something the man about to show him the house doesn’t know. With that, we’re introduced to the Arringtons: Phil, Velma, his daughter Livia (from a previous marriage), and his youngest, Madeline, soon to be born. They’re cosmopolitan. Sophisticated. They’re also troubled, arrogant, and throughout the linked stories, falling apart.

We follow the family as Phil begins his private practice, as Velma opens her antiques shop, and as they buy new homes, collect art, go skiing, and have overseas adventures. It seems they’ve made it in the white world. However, young Maddie, one of the only Black children in town, bears the brunt of the racism and the invisible barriers her family’s money, education, and determination can’t free her from. As she grows up and realizes her father is sleeping with white women, her mother is violently mercurial, and her half-sister resents her, Maddie must decide who she is despite, or perhaps precisely because of, her family.