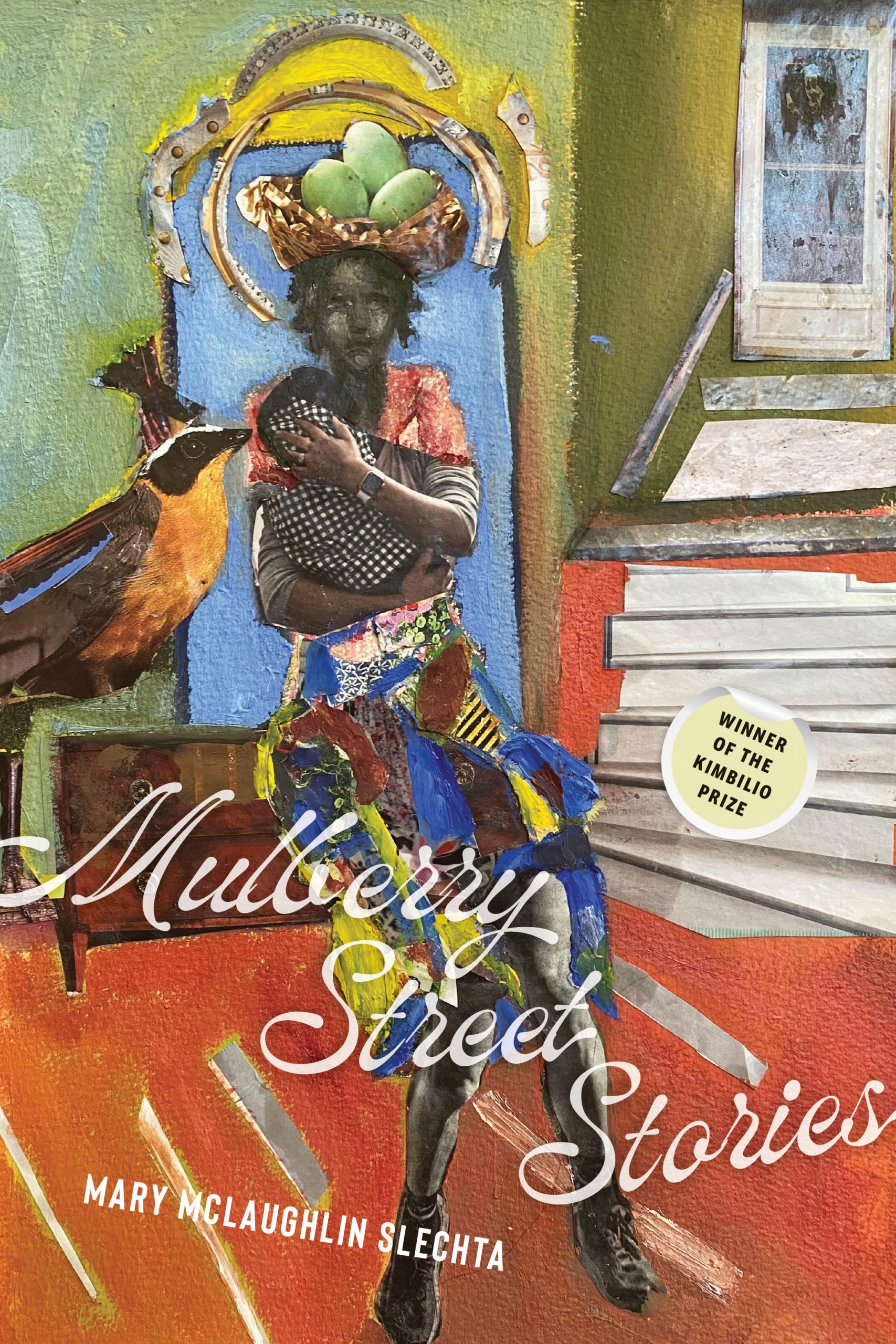

MULBERRY STREET

Winner of the Kimbilio National Fiction Prize

A New Collection from kimbilio Fellow Mary Slechta

Mulberry Street is an African-American neighborhood with a disputed past: is it the result of white flight, a tenuous foothold for southern transplants, or a sliver spun off during the creation of Earth and once ruled by a god named Mr. Washington? The stories, connected sometimes by character and plot and always by geography, are told by and about its residents who, despite not in possession of a definitive history, have, in another sense,“seen it all”: not just the generational damage from forced migration, redlining, gentrification, racial profiling, over-policing, and other aspects of systemic racism, but, like the child in Seuss’ picture book, also the fantastical. Among the latter are children falling off the flat world; a vampire posting himself like Henry Box Brown; the ghost of the “first black meter man” taking credit for triggering white flight; and a husband building a maze to trap the “somethin,” the faceless racism that has plaqued his family and threatens his wife. Several characters reappear at different stages of life, spotlighting the impact of trauma over time on the individual and the community. A central trauma is The Fire, an attack by white vigilantes as seen from the perspectives of a woman with a talking belly, a vampire burned in his casket, a resident blamed for the the fire, and a huckster selling rebrowning cream.The perspectives help explore how trauma awakens the grifter as well as the saint, and how reparations, although important, cannot repair damage to the soul.

Another recurring motif are cracks, in the asphalt and memory, which signal both destruction and hope that a new Mulberry is being born. Beginning with the start of Mrs. Washington’s atonement for the lost children, the collection ends with an ode to Toni Morrison’s project to elevate untold stories. In “A Bench on the Moon,” Marjorie, a southern transplant and griot charged with remembering things exactly as they happened, is in the mid-stages of Alzhemeir’s. Wandering away during a fugue, she is drawn into music spilling from a bar and claims to be a storyteller named Toni. The bartender and patrons, hang on every word of her intriguing tales, one of them resting his hand on her arm “like a penny on the arm of a record player” to keep the disjointed stories together. In this way the promise of a new Mulberry Street is fulfilled.