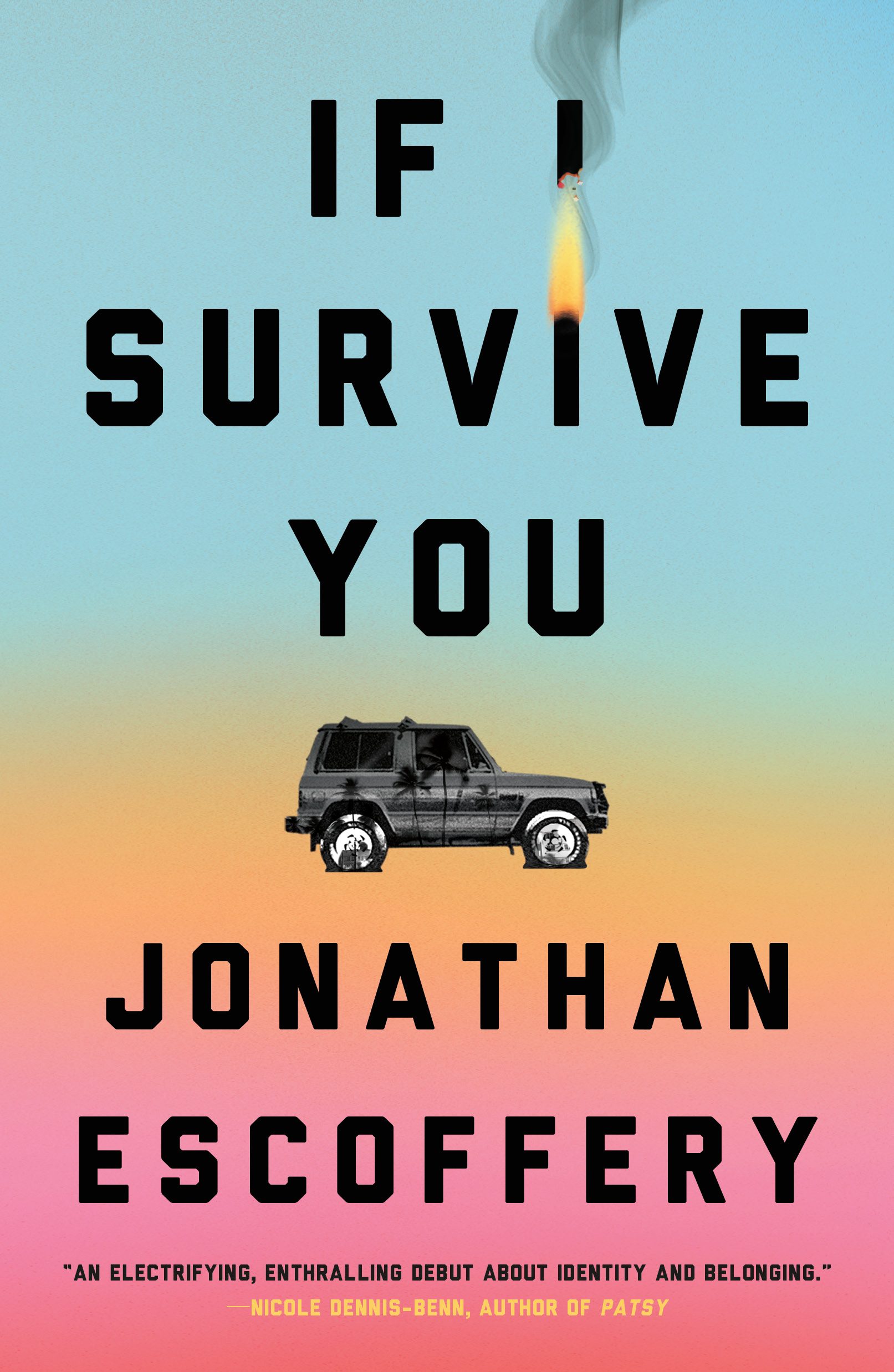

If I Survive You

THE NEW collection from kimbilio fellow Jonathan Escoffery

In the 1970s, Topper and Sanya flee to Miami as political violence consumes their native Kingston. But America, as the couple and their two children learn, is far from the promised land. Excluded from society as Black immigrants, the family pushes on first through Hurricane Andrew and later the 2008 recession, living in a house so cursed it’s begun sinking into the hill it sits atop. But even as things fall apart, the family remains motivated, often to its own detriment, by what their younger son, Trelawny, calls “the exquisite, racking compulsion to survive.”

Constructed with heart and humor, If I Survive You centers on Trelawny as he struggles to carve out a place for himself amid financial disaster, racism, and flat-out bad luck. After a fight with Topper—himself reckoning with his failures as a parent and his longing for Jamaica—Trelawny claws his way out of homelessness through a series of odd, often hilarious jobs. Meanwhile, his brother, Delano, attempts a disastrous cash grab to get his kids back, and his cousin Cukie searches for a father who doesn’t want to be found. As each character searches for a foothold, they never forget the profound danger of climbing without a safety net.

Pulsing with vibrant lyricism and inimitable style, sly commentary and contagious laughter, Escoffery’s debut unravels what it means to be in between homes and cultures in a world at the mercy of capitalism and white supremacy. With If I Survive You, Escoffery announces himself as a prodigious storyteller in a class of his own, a chronicler of American life at its most gruesome and hopeful.