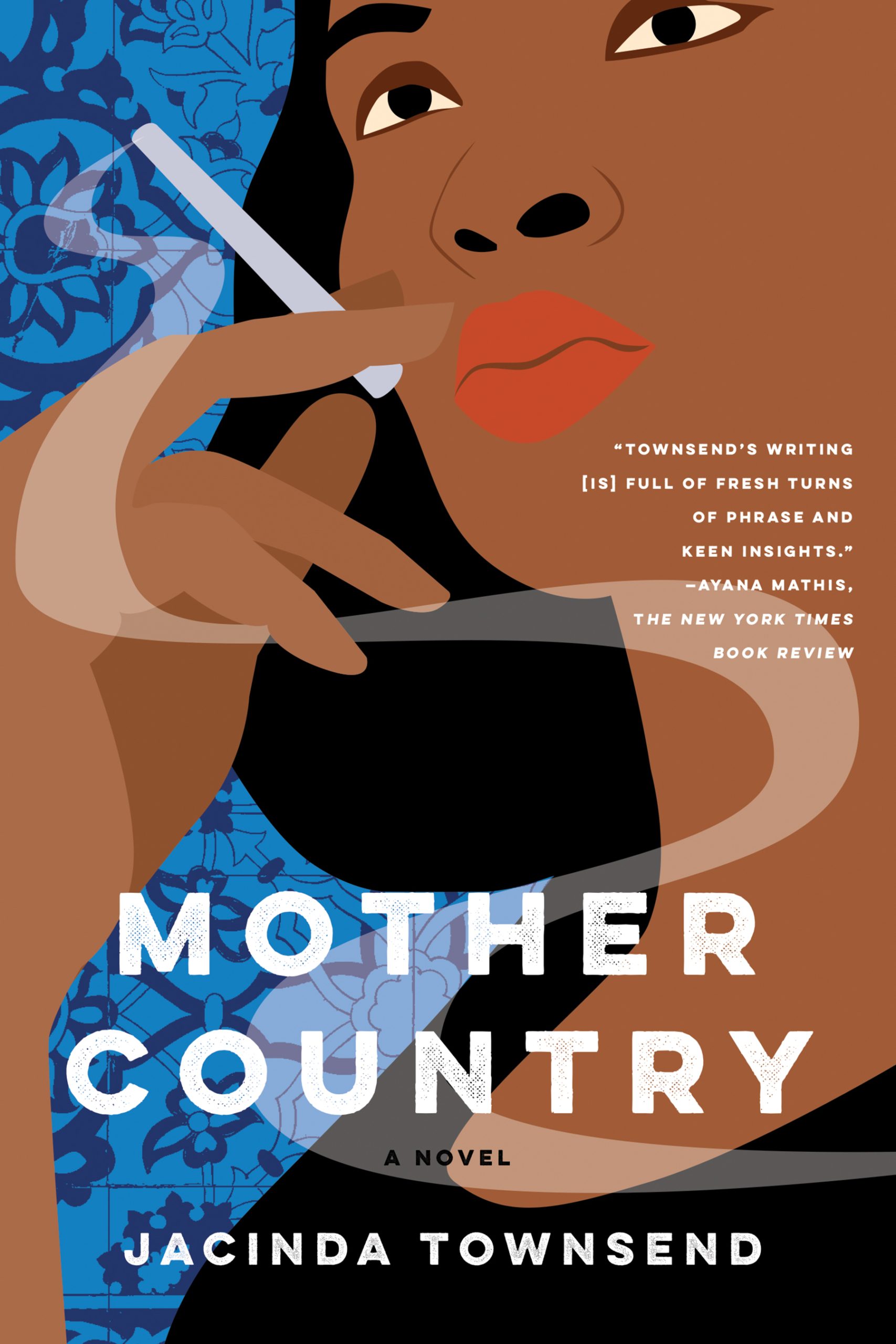

Mother Country

THE NEW novel from kimbilio faculty member Jacinda Townsend

Saddled with student loans, medical debt, and the sudden news of her infertility after a major car accident, Shannon, an African American woman, follows her boyfriend to Morocco in search of relief. There, in the cobblestoned medina of Marrakech, she finds a toddler in a pink jacket whose face mirrors her own. With the help of her boyfriend and a bribed official, Shannon makes the fateful decision to adopt and raise the girl in Louisville, Kentucky. But the girl already has a mother: Souria, an undocumented Mauritanian woman who was trafficked as a teen, and who managed to escape to Morocco to build another life.

In rendering Souria’s separation from her family across vast stretches of desert and Shannon’s alienation from her mother under the same roof, Jacinda Townsend brilliantly stages cycles of intergenerational trauma and healing. Linked by the girl who has been a daughter to them both, these unforgettable protagonists move toward their inevitable reckoning. Mother Country is a bone-deep and unsparing portrayal of the ethical and emotional claims we make upon one another in the name of survival, in the name of love.